Return on community (ROC) is the brainchild of Tony Hsieh [pronounced “Shay”], the CEO of Zappos, and author of Delivering Happiness.

When Mr. Hsieh and his team decided to establish a corporate campus to house the company’s three buildings and provide room to grow, he selected an urban setting instead of an isolated corporate campus. By acquiring the former Las Vegas City Hall and its twelve acres of land, he placed his business in the heart of the city. His ultimate vision is for a campus that influences, and is influenced by, the city around it.

Mr. Hsieh said that instead of an insular approach, he and his team took an NYU approach that seamlessly blends a campus with the city around it. As a former student at NYU’s film program, I can attest that this concept creates an extraordinary learning environment because the classroom setting is supplemented by a thriving, dynamic, and very real urban center.

At $350 million, the company’s commitment to revitalizing downtown Las Vegas is significant. That amount includes $100 million in real estate, $100 million in residential development, $50 million in small businesses, $50 million in education, and $50 million in tech startups through the VegasTech Fund.

A unique vision

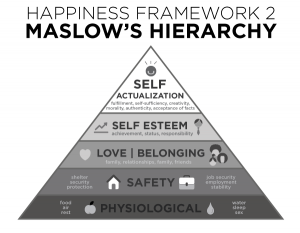

To understand Mr. Hsieh’s belief in ROC, it is necessary to first understand his belief in happiness as a business objective. He says that happier employees create a better brand experience, and if he is able to perfect the culture, everything else will fall into place.

Culture is the number one priority of the company. A company’s culture and a company’s brand are really just two sides of the same coin.

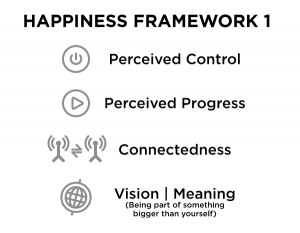

In his book Delivering Happiness, Mr. Hsieh illustrates his vision for workplace enjoyment:

To judge whether happiness is good for business, take a look at a few numbers:

- Fortune magazine’s list of “100 Best Companies To Work For” ranked Zappos at number 6 in 2011 and number 11 in 2012.

- When Amazon bought the company in 2009, it reported $1 billion in annual merchandise sales

- Mr. Hsieh’s book, Delivering Happiness, has been translated into 20 languages.

Listening to Mr. Hseih, it is easy to see how his commitment to workplace happiness translates to an open campus that connects employees’ personal lives with their work lives.

I think a lot of companies have the assumption that work has to be unenjoyable. ..That leads to this whole thinking of work/life separation and work/life balance. The implication there is that work must not be fun.

Here, we think of it in terms of work/life integration. At the end of the day, it is just your life.

Quantifying value

This leadership vision that business success hinges on an enjoyable and individually fulfilling culture reflects a strikingly untraditional mindset and management style. Expounding on that concept and applying it to measurement, essentially challenging the accepted notion of ROI as the standard means of assessing value, represents a significant departure from established management practices.

Tim O’Reilly, the founder and CEO of O’Reilly Media, has long challenged traditional notions of quantifying business value. He says it is something he has thought about since reading an article in 1975 called the “Clothesline Paradox,” by Steve Baer.

The thesis is simple: You put your clothes in the dryer, and the energy you use gets measured and counted. You hang your clothes on the clothesline, and it “disappears” from the economy. It struck me that there are a lot of things that we’re dealing with on the Internet that are subject to the Clothesline Paradox. Value is created, but it’s not measured and counted. It’s captured somewhere else in the economy.

From the standpoint of measuring value, Mr. O’Reilly is saying that traditional business metrics are, in some cases, too limiting.

Our accounting doesn’t necessarily match the real world, says Mr. O’Reilly.

Accelerating innovation

Zappos’ vision for reinventing a section of Las Vegas is called The Downtown Project and its mission is to: “help transform Downtown Las Vegas into the most community-focused large city in the world.”

The Downtown Project website describes this investment as a big bet based on three guiding principles: collisions, community, and co-learning, which are designed to accelerate serendipity, learning, productivity, and innovation. This is where Mr. Hsieh may be onto something vital to many businesses in our evolving and uncertain economy.

According to companies that assess workplace engagement, a chief complaint from employees in 2013 is change fatigue. Essentially, companies are struggling to adapt to changes in their marketplace and, therefore, undergo a series of successive organizational realignments. This process is taxing on employees and managers alike.

As a student of the financial crisis and its effects on consumer preferences, this employee perspective does not surprise me. Consumer preferences changed dramatically during the crisis and perception of individual wealth plummeted. As a result, customers today are more interested in experience than ownership, which is not congruent with traditional, high-margin product strategy.

More insular businesses, those whose cultures draw their thinking inward, are less apt to understand the drivers of economic change. Consequently, these organizations are adapting to change slowly and painfully through a series of reorganizations that leave managers feeling as confused as their teams.

A more outside-in approach, which Zappos community-based culture fosters, can help employees maintain a workplace mindset that is more tuned in to life outside the company. It also enhances their ability to innovate and adapt in step with consumers. Zappos’ principles of collisions, community, and co-learning can in fact accelerate innovation, learning, and productivity. And, it may just be the ideal business model for coping with uncertainty.

Many businesses are reaping rewards from similar, sustainable business practices commonly attributed to the Sharing Economy. A prime example is AirBnB, a company that launched in 2007 and in 2012 claimed to have booked more rooms than the Hilton hotel chain.

What do you think?

Is Zappos’ new corporate campus a vision other companies should emulate or is it just a risky bet from a well-intentioned CEO? The potential benefits to culture and innovation seem clear, however, do they justify a $350 million initial investment in a city, which ostensibly should be supported by its tax base?

There’s more to this story,and I’m curious to know the opinions of my readers. Let’s hear your thoughts.

Hi Kelly,

Interesting business case!

Seen from the perspective that reputation is an indicator of trust, I believe Mr. Hsieh’s vision is an example of reputation management in its true meaning; creating business transformation.

I consider the redesign of his companies culture and investment/innovation policy as Mr. Hsieh’s way of making sure Zappos’ interests better coincide with those of his internal and external stakeholders.

In this way it could be considered as an example for other companies urging to increase the level of trust with their stakeholders.

Whether it’s worth $350 million is hard to say since I’ve no idea what other options might cost, including expensive alternatives to further strengthen Zappos reputation.

Kind regards,

Chris Roelen

Twitter: @ChrisRoelen