Over the past several years, I’ve studied the role of trust in massive social and environmental crises and two remarkable events stand out from the pack: the BP Oil Spill (Deepwater Horizon) and the Chilean Mine Rescue.

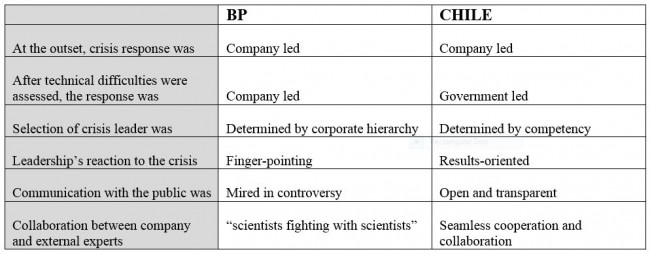

By comparing these events, it’s easy to see how corporate culture influences crisis management. Moreover because the crises occurred in different hemispheres and required the help of experts from a variety of different backgrounds, their comparison illuminates the role of culture more broadly.

By comparing these events, it’s easy to see how corporate culture influences crisis management. Moreover because the crises occurred in different hemispheres and required the help of experts from a variety of different backgrounds, their comparison illuminates the role of culture more broadly.

In fact, social norms affect how citizens, companies, and governments organize to solve some of the most daunting humanitarian and environmental crises on our planet. Comparing these two specific events reveals how in the U.S. and more specifically–inside BP’s corporate hierarchy, culture clearly hindered progress. However in Chile, culture enabled one of the most successful rescue missions ever.

Culture in the Spotlight

During times of great turbulence, the truth often rises to the surface. Extreme stress drives people and organizations into a state of decision-making that Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman refers to as “System One,” in his book Thinking Fast and Slow. This impulsive and emotional state of decision-making is common when people are under stress, lacking sleep, and anxious. Therefore, the things people do and say everyday, their habits or automatic reactions, take over. And in poor ethics and values cultures , these default behaviors are not suitable for public scrutiny.

In many respects, Tony Hayward, BP’s former CEO, is now an iconic example of how unhealthy cultures produce incapable leaders. John Bell, the former CEO of Jacobs Suchard, which is now part of Kraft Foods, adeptly describes Mr. Hayward’s failures on his blog:

The entire world was touched by the most environmentally destructive crisis of all time – BP’s oil spill in the Gulf. Everyone watched as CEO Tony Hayward made blunder after blunder while BP’s crude killed. Three weeks after the explosion, Hayward called the spill “relatively tiny” in comparison with the size of the ocean – 6 weeks later he said he’d like his life back, and 6 weeks after that, BP’s shell-shocked Board finally put him out of his misery.

As details emerged in the months and years following the incident, it became clear that Mr. Haward’s actions reflected the company’s culture at the time. It was later revealed that BP had never created an actual crisis management plan for the rig. During the drilling, managers had ignored warning signals, preferring instead to stay on schedule. And, Transocean later claimed that BP intentionally concealed the rate of oil flowing from the Macando well during the first months of the spill. These are all examples of culture. As Elizabeth Hass Edersheim described in the Harvard Business Review:

Culture is an organization’s operating system, the values that everyone lives by. In the case of BP, the culture didn’t work effectively and now its failure is on full display.”

Quite remarkably, it’s the positive side of culture that made the Chilean Mine Rescue such a triumphant success. Whereas BP sought to control information and scientific discovery during the crisis, the Chilean Mine Rescue benefited from specialists and technology from around the world. Through a masterfully coordinated effort, the relatively poor and technically inferior nation succeeded in saving all 33 men in almost 20 days less time than it took BP to shut down the Macando well.

Commonalities between BP and Chile

At first glance, these events seem to have little in common, but when you dig a little deeper, some fascinating insights emerge. Both events occurred in environments where businesses have little or no experience solving problems: thousands of feet under water and rock. Successful leadership depended on deep technical expertise and on-the-spot innovations, including the development of new technology. And, as Mr. Bell referenced above, both events were watched by the world.

While one was an environmental crisis and the other a humanitarian crisis, both directly resulted from business actions. This is an important distinction from natural disasters, which tend to elicit greater levels of sympathy and contribution from businesses and civic groups. A man-made event, however, is often steeped in resentment and anger, at least here in the U.S.

Cultural differences have enormous influence

The differences between how these crisis responses were orchestrated are compelling. With the BP disaster, research reveals constant argument and battles for control between business, government, and technical experts. According to a report from Scientific American:

Scientist fought scientist in the battle over whether to proceed with an established way to plug the leak, the so-called “top kill” operation. Nobel Prize winning physicist and U.S. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu remained unconvinced of BP’s technical case, whereas geologist by training Tony Hayward, CEO of the British oil major, felt it had as much as a 70 percent chance of success.

By contrast, the Chilean rescue effort benefited from an almost seamless coordination of effort between specialists, including NASA and drilling experts from a dozen or so countries. From the outset, the country’s newly elected president, Sebastian Pinera assumed control of the rescue and assembled a leadership team of experts from several different companies. Andre Sougarret, a mining engineer with crisis experience was handpicked to lead the rescue.

Three Harvard researchers: Faaiza Rashid, Amy C. Edmondson, and Herman B. Leonard published a case study called: “Leadership Lessons from the Chilean Mine Rescue,” which details Mr. Sougarret’s remarkable leadership techniques and his ability to balance technical knowledge with collaborative and empowering team-building. His adept leadership skills almost certainly are responsible for the miners’ safe passage to the surface after 68 grueling days underground.

The Chilean rescue effort

- As many as three different teams drilled at the same time, using different technologies and different tactics. These were known as plans A, B, and C.

- The teams sought technical knowledge and ideas from organizations such as the United Parcel Service and the Chilean Navy.

- The teams also welcomed help from those that offered it, such as Maptek, an Australian 3-D mapping software company.

- Mr. Sougarret “created a psychologically safe environment, never blaming anyone and always focusing on the learning generated by failure.”

- Innovation occurred frequently, experimentation was welcomed, and learnings were quickly absorbed by the full team.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the HBR case study by Rashid et al. is their focus on iterative decision-making. In the U.S. very few organizational cultures are accepting of iterative design and implementation processes. The basic structure of organizations is not conducive to this level of agility. Ms. Rashid and her team explain this clearly,

It isn’t easy for leaders to make the shift to an iterative process; most cultures and systems will stifle their attempts. . . Executives will have to shed the deeply embedded beliefs that important business challenges and opportunities are well defined.

Cultural Comparison: At-a-glance

photo credit: Deepwater Horizon Response via photopin cc