Last week, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) set a new record high, closing the day at 14,253.77. Only four years ago this March, the market hit bottom during the financial crisis, closing at 6,547.05. It was the market’s lowest level in twelve years, and those forfeited market gains became known as the lost decade in stocks.

Surprisingly, the fear and trauma of March 2009 is not counterbalanced by euphoria in March 2013. Just three days after the market hit a new high, the U.S. Department of Labor’s monthly jobs report revealed that unemployment had reached a four-year low. Yet these numbers generated relatively little news, which raises an intriguing question: What happened to the hubris of good numbers?

Have Americans become immune to these indicators of prosperity or have we simply lost our penchant for reckless daydreaming? To understand today’s sober response to market gains requires more than an assessment of corporate profits and European instability. Although the financial crisis is four years in the past, the disappointment and disillusionment of that catastrophe has a lasting impact on American culture. By appreciating the human toll of the crisis, we are able to provide meaningful context for today’s events.

As it turns out, the decades of economic growth prior to the financial crisis affected Main Street and Wall Street very differently. While the culture of global finance became increasingly impersonal during this period of roaring market growth, individual investors unknowingly became increasingly vulnerable to a range of technical issues they barely understood. When the crisis hit, those differences led to a widespread sense of distrust.

Part I of this two-part series chronicles regulatory and business changes that shaped how Americans prepare for a financially secure retirement. Part II, to be published next week, illuminates changes to the corporate culture within some global financial firms, what Allan D. Grody refers to as “Culture Gone Awry.”

Part I: How retirement investing became personal

In 1980 Ted Benna, a benefits consultant, discovered a new tax-advantaged savings opportunity in the Internal Revenue Code, Section 401(k). In 1981, the IRS sanctioned this new pre-tax employee retirement savings vehicle and nine companies began implementing these plans that same year. The industry took off quickly and according to the Investment Company Institute, in 2012 more than 50 million Americans held a 401(k) representing an estimated $3.5 trillion in retirement savings.

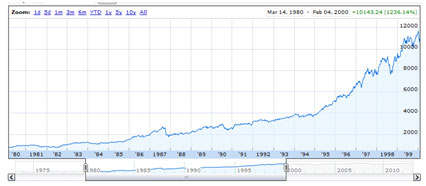

Two concurrent events influenced rapid adoption of the 401(k). First, in the early 1980s, the stock market began a growth spurt that lasted for two decades and consequently caused many first-time investors to feel capable of amassing a sizeable nest egg through their efforts.

1980 to 2000: Two Decades of Growth

Second, corporate pension plans turned out to be a dismal liability on business’ balance sheets. Companies were unable to fund pensions because their workforces were shrinking which meant that the dependency ratio of retirees to working employees was unsustainable.

For example, in 1962, General Motors had 464,000 U.S. employees and 40,000 retirees creating a manageable dependency ratio of 11.6 employees for each pensioner. By contrast in 2011, General Motors employed just 70,000 employees whose productivity needed to fund pensions for 700,000 retirees. The company’s new dependency ratio was untenable, leaving just one worker for every ten pensioners.

Understandably, corporations were eager to transfer this risk and responsibility to individuals. Employees, for their part, felt empowered to invest for their retirements with company contributions and the new portability features of the 401(k) meant they could change jobs without forfeiting their accrued value in a pension plan.

However, in 2008, investors’ do-it-yourself joyride came to a screeching halt. This disillusionment occurred while political and economic leaders grappled with an extremely complex crisis which included opaque solutions (e.g., TARP) and remarkably few criminal indictments. In effect, millions of Americans experienced a deep sense of fear about their own financial futures without a clear sense of culpability. By and large, no one was held directly responsible for their tauma.

In crisis communications, we study the dimensions of fear and develop both messages and tactics that rapidly alleviate fear and restore confidence. Among these tactics are evergreen principles such as transparency, candor, clarity, speed, and empathy. Some of these tactics are applied to messaging, others are applied more strategically. The response to the financial crisis, from business and government left Americans feeling more confused and less confident.

Perhaps the most notable aspect to bear in mind is how personal and emotional these issues are for many Americans. Not too long ago, investing was reserved for those with disposable income. It was an activity for wealthy Americans who wanted to preserve wealth for future generations. Today, however, the most uninformed and uneducated among us are charged with investing for financial security in retirement. Both the players and the rules of the game have shifted markedly.

When the market climbed for over two decades, investing led to hubris because it was not based in fear. As Allan Grody cites from another writer: the culture within banks shifted from “hate to lose” to “love to win.” Individual investors shared that same attitude.

Today, the pendulum has swung the other way.

Part II: How global finance became impersonal

Next week, we’ll assess the market influences and business decisions that diminished corporate culture and values prior to the crisis.

Leave a Reply